“All Models are wrong. Some models are useful.” – Edward Deming

“There is nothing so practical as a good theory.” – Kurt Lewin

Any long-term solution to addictive behavior must be based on the recognition that for many people, addiction is a chronic, life-long challenge that requires varying amounts of intervention over a lifetime. Most research on the effectiveness of addiction treatment has focused on short-term outcomes, which unfortunately has led to misconceptions about the overall value of treatment. Whether the outcomes turn out good or bad, the end result is based on a narrow snapshot of time that does not capture the enduring nature of addiction. Fortunately, there is now increased attention on what is known as “addiction careers” and “treatment careers.” The word career may seem a bit strange, but it is used to describe the initiation, development, maintenance and cessation of addictive behavior over a lifetime. Studying both addiction and treatment careers have provided a much clearer understanding of the nature of addiction, but more importantly has pointed clearly to a life-long management approach over a short-term treatment focus for many people.

A common myth about addictive behavior is that it follows a pattern of progressive escalation over time. Some have even suggested that the “disease” continues to progress even if a person remains abstinent from the behavior. The career approach has revealed that although addictions may progress over time, there are usually many peaks and valleys along the way, and often long periods of sustained abstinence between times of engaging in an addiction. This is not to say that people don’t permanently end addictive behavior – many do – but few accomplish the feat without multiple attempts. There appears to be no one course that addiction follows, but instead many differing paths that wind through a person’s life. Why it begins and why it ceases has been the focus of much research, and there are still no absolute answers. What is clear about the nature of addiction is that for many it comes and goes over time, and the “why” is still somewhat of a mystery (see understanding addiction).

Society in general, along with other systems including primary care medicine, the legal system and policy makers have been disappointed by the fact that most addicts return to their addictions even after receiving treatment. Research has shown that by the end of the first year following a treatment episode most return to their addictive behavior, and many back to pretreatment levels. This has been used as evidence that treatment does not work. One of the most distinguished addiction researchers in the country, A. Thomas McLellan, has pointed out that the issue of treatment effectiveness is only relevant when it is compared to something. He argues convincingly that the manner in which most people have historically evaluated treatment is based on what happens after a person completes a program. If we examine what happens during treatment, we find that most people do quite well. They greatly reduce or give up completely their addictive behavior and show improvement in many other areas of their life. When treatment is complete clients are expected to follow-through with what they learned in the program and stay committed to their recoveries – which almost always includes aftercare in the form of 12-step meetings. For many people this does not happen for long. They relapse, and this becomes the evidence that treatment failed. Even more, it reinforces a belief system that nothing will change the addictive behavior and in the end, treatment really makes no difference. The end result is a revolving treatment door where addicts become increasingly more difficult to help with each successive treatment episode. If this sounds backwards…common sense says it should be easier for a counselor to work with someone who already has some idea about treatment than someone who is coming through the doors for the first time. Sadly, it is often those who have had the most treatment that are the most resistant and defensive about being back in treatment because of their belief that it makes no difference. The main point, is that evaluation of treatment “during” looks very different from “after.”

How does a physician determine the effectiveness of a medication? Imagine a patient who monitors his blood pressure over a period of weeks and learns that he meets criteria for severe hypertension. He is appropriately placed on an anti-hypertensive medication and soon his blood pressure is now registering in the normal range. But what happens when the medication is taken away? Predictably, his blood pressure returns to pretreatment (or pre-medication) hypertensive levels. This is one way physicians evaluate how well a medication works. Now, think about addiction treatment and how we evaluate it. When a person is in treatment (like being on the medication), they do very well. But once they are discharged (medication is stopped), most people return to their addictive behavior. Instead of concluding that treatment has a limited impact on addictive behavior, it is clear that in fact it has a significant impact on behavior while a person is engaged in treatment! What are the implications then for how to best manage addictive behavior?

The most important implication is the need to shift from treating addictions with an acute model of care to a continuance of care model. This means stopping the revolving door, and finding innovative ways to keep those who struggle with addictions connected to some form of treatment or addiction management system for long periods of time. Remember our hypertensive patient? Do you think his physician would stop seeing him after six months just because his condition was now under control as a result of the medication? Absolutely not! The man would remain a patient indefinitely and always stay connected in some way to a medical provider. This type of care is the norm in the medical field for chronic conditions like asthma, diabetes, and hypertension because it makes sense both to the patient and physician. A similar continuance of care model is desperately needed in the treatment and long-term management of addictions. Let us now examine in more detail exactly what is meant by addiction management and how this would work.

Addiction management is defined by the various methods, tools, resources, and approaches that are used throughout a lifetime to manage addictive behavior. Treatment can be a very important component of addiction management, but not a requirement – as many people successfully change behavior using other methods. The basic tenants of addiction management include:

Addiction Management Principle

Model:

Continuance of care emphasizing long-term life management of addictive behavior.

Approach:

Because people are different and their needs change over time, the approach is individualized and dynamic. It also addresses the multiple needs of a person concurrently, not just the addictive behavior – so it is both comprehensive and integrated.

Goal(s):

Based on individual needs and may change over time. Includes abstinence, harm reduction and controlled use or moderation management – but also includes goals related to life beyond addiction.

Professional Treatment:

Multiple pathways and modalities utilized, with no one method or approach being more effective than any other – all work equally about the same. Also, not a requirement for successful behavior change.

Behavior Change:

Occurs as a result of various underlying processes that can be utilized with or without treatment – although treatment works best when it is based on these natural processes.

Defining Outcomes:

Multiple measures including reducing or stopping addictive behavior, developmental growth, increased quality of life, physical and mental health, among others.

Medication(s):

Used appropriately and made available to all who need them.

Addiction over time:

For most people it “comes” and “goes” throughout a lifetime with many peaks and valleys – but can remain stable and managed for long periods of time. For some, a point can be reached when it no longer makes sense to even call it addiction management, but instead just “life.”

Aftercare:

Aftercare is what happens after treatment and almost always is synonymous with 12-step meetings. In addiction management there is no “after-care” only “continued-care” that is delivered in many different ways over a life time – rarely utilizing the 12-step programs.

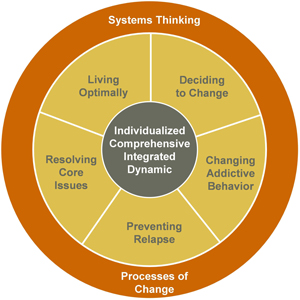

Although these ideas constitute the foundation of addiction management, the essence of the approach is summarized in the model below.

At the center are the principles that guide the approach to addiction management:

Individualized: No single approach is appropriate for all people. Each person presents a unique history, and ideally creates a program tailored to his/her specific needs and tastes. For some, that will include professional treatment, for others it may mean a consistent practice of meditation and time with a guru. The paths can look very different, but the underlying purpose remains successful long-term management of addictive behavior.

Comprehensive: Effective addiction management attends to the multiple needs of a person, and does not just focus on the addictive behavior. Often this includes issues related to mental or physical health, employment, finances, relationships, housing, legal problems and spirituality.

Integrated: Not only does addiction management address multiple needs, but to be successful the needs must be addressed in an integrated manner – meaning they are addressed concurrently. Many professional treatment programs separate the treatment of addiction and mental health issues, when in reality the two are very interconnected. A physician would not say “let’s treat your asthma now, and once it is under control then we will address your diabetes.” Unfortunately, many people in treatment are told they should only focus on one thing at a time.

Dynamic: It is no secret that people change over time – whether it is intentional or not. What works for awhile may become stale or stop working. Addiction management assumes that over time adjustments will need to be made as to how a person manages their behavior. Even more, it recognizes that part of human nature is to grow, develop, and evolve – which can occur within the framework of addiction management.

As these principle guide the approach, the work of long-term addiction management falls into one of five areas. Although discrete in the model above, in reality there is considerable overlap as people will find they have their hands in different areas at the same time. In addition, despite the sequential clockwise arrangement of the components starting with deciding to change, in most cases change does not unfold so neatly. A brief summary of each area follows:

The Five Factors

Deciding to change: Changing any addiction requires some commitment to do so. But the very nature of addiction is being caught in a state of ambivalence that often keeps a person stuck. This first component includes all the resources, interventions, and approaches that facilitate resolution of ambivalence in the direction of positive change. The essence of this area of work is building motivation to change, increasing commitment to the process, and developing the necessary resources to take the next step in changing addictive behavior.

Changing addictive behavior: With ample motivation and commitment to change, the work of this component is on actively changing the addiction. The goal may be complete abstinent or harm reduction, but the end result is positive behavior change. There are many methods for changing addictive behavior, but no one method that is superior. Instead, the strategy is to find which methods work best for a particular person at a particular point in time. In the end, changing an addiction is a fairly straightforward process that is far easier than many believe. What is more difficult is maintaining that change over long periods of time….read on…

Preventing Relapse: Once a person has successfully changed their addictive behavior, the real key is maintaining that change. Relapse prevention has typically been focused on identifying the triggers and cues that initiate addictive behavior, and then developing strategies for overcoming them. During the past decade this area of work has expanded to include emotion management skills, developmental resources, and the realization that relapse is a human phenomenon not just an addict experience (consider how many people break New Year’s resolutions). In addition, relapse is not a black and white issue, but is best understood as a process with many intervention points. Understanding how to prevent relapse and what to do if it occurs are both critical to long-term success. But even the best relapse prevention programs fail when core issues remained unresolved…

Resolving Core Issues: Very often addictive behavior is fueled by unresolved core issues that have in common emotional pathology. To succeed at long-term addiction management it is absolutely necessary to address core issues to the point of resolution. These issues may include trauma (sexual, physical, emotional, etc.), grief, developmental deficits or constrictions, or family of origin experiences. They are so common that no person is free from them. Although they are opportunities for growth, unfortunately they often remain unidentified even after multiple treatment episodes. Also, it is not uncommon for those in recovery to suppress, ignore or disconnect from them due to fear. Like changing addictive behavior there are many methods for resolving core issues, and some may be extremely difficult to change without professional help. But stopping addictive behavior and resolving core issues often brings up another challenge…

Living Optimally: It is not uncommon in the process of long-term addiction management to face crossroads where there exits a great deal of confusion about the purpose of life, the role of spirituality, and what the big empty hole inside is all about. Where before it was filled with the addiction, now work needs to be done to become whole. This is the area that focuses on how we spend our time and energy. Optimizing life is a constant challenge, and this area of work draws on many disciplines including sociology, theology, anthropology, biology, and psychology to name a few. It has been written about countless times over the centuries, yet the wisdom remains practically the same.

The above five content areas are further understood and enhanced by Systems Thinking and the Processes of Change.