When a doctor tells me that he adheres strictly to this or that method, I have my doubts about his therapeutic effect…I treat every patient as individually as possible, because the solution of the problem is always an individual one. – Carl G. Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections

The greatest challenge today…in all of science, is the accurate and complete description of complex systems. – Edward Wilson

Successfully overcoming addiction begins by gaining a clear understanding of the:

- Factors producing the addictive behavior

- Issues that co-occur with the addictive behavior (e.g., mental health, physical, legal, social)

- How all of the factors interact together to produce the current behavior patterns

Gaining this information is not easy, and in fact, most who have been through professional treatment programs rarely are evaluated to the extent necessary to achieve long-term successful outcomes.

The most significant problems with most professional treatment evaluations include:

1) Objects

The over-emphasis on evaluation of specific objects of addictive behavior while ignoring others (i.e., focus on alcohol and drugs while ignoring gambling, sex or food).

A corollary to this is not evaluating how various objects are often used together (e.g., methamphetamine and sex, gambling and alcohol, television and marijuana, food and nicotine).

2) Not evaluating

Screening for mental health diagnoses, but not actually evaluating thoroughly enough to be able to diagnose (Note: this is one problem with the most widely used addiction assessment instrument the “Addiction Severity Index”).

3) Interactions

Little thought given as to how various diagnoses interact, or are packaged together, to produce the problematic behavior patterns. This requires the ability to think systemically – a clinical skill often underdeveloped.

This is important, because instead of treating many issues independently, it is much more effective to find natural leverage points for change and intervene on specific issues that ultimately impact the entire person (or system).

4) Strengths

Very little attention is given to assessing individual strengths, including optimism, hope, love and empathy – all factors vitally important in the long-term management of addictive behavior .

5) Developmental level

They often lack any framework for assessing an individual’s developmental level. Because good treatment outcomes require the ability to initiate, form, develop, and maintain healthy intimate human relationships, it critical to know where a person is constricted developmentally. Absent any formal process for considering a person’s emotional maturity (intelligence), knowing how to intervene developmentally is challenging.

6) Access

They are never shared with clients (when HIPAA laws specifically state that all clients have a right to everything in their file). In almost all cases, clients should be given copies of their evaluations to read, comment on, and process. Instead, most treatment programs complete the evaluation for insurance purposes – or as a precursor to a treatment plan – and then stick it in the chart never to be seen again.

By allowing clients to read their evaluations it offers them a chance to make necessary corrections (building the therapeutic relationship), see their life in a useful framework, and comment on the emotions that arise when reading such an assessment.

The importance of a clinician’s skills

At this point, it should be clear that useful evaluations involve careful consideration of many factors. They also involve important clinical skills, including:

- Ability to connect with a client in a trusting way so that they will reveal necessary and accurate information

- Knowing which clinical assessment measures to use

- How to evaluate prior treatment evaluations/assessments

- Who other than the client should be consulted regarding the client’s behavior (e.g., spouse, children, employer, judge)

- Knowing when to collect biological samples

So what is the optimal evaluation?

Unfortunately, the field has yet to produce any single tool that does everything well. Many treatment programs and private practice clinicians piece together various tools, and do their best with the resources available. But as a field, we can (and should) do better.

As a start, the following link provides a template evaluation where many of the pieces discussed above have been incorporated. It’s not perfect, but meant as a starting point for anyone who would like to see what a comprehensive evaluation might look like.

If you struggle with addiction please use it as a guide to assess various aspects of your behavior and life.

Comprehensive Evaluation

Please note the above template does not address three critical issues:

- Assessing positive traits

- Evaluating developmental levels

- Dealing with biological samples or other empirical measures.

Assessing Positive Traits

As mentioned above, the best evaluations focus more on just the pathological. They include questions and measures that assess individual strengths that can be used in designing long-term management programs.

One of the best websites for learning more about evaluating positive traits is managed by Dr. Martin Seligman and focuses on Authentic Happiness. For clinicians, a useful text is produced by the American Psychological Association and titled Positive Psychological Assessment: A Handbook of Models and Measures.

Evaluating Developmental Levels

There exists a plethora of methods for understanding and evaluating developmental levels/stages. Many developmental theorists focus on particular aspects of development, including:

- Piaget – cognitive

- Erikson – psychosocial

- Kohlberg – moral

- Bronfenbrenner – ecological

These should be familiar to therapists. One particularly useful way of understanding development that therapists and those struggling with addiction have likely not heard about is proposed by Dr. Stanley Greenspan. His six developmental stages (or functional levels) provide a framework for understanding the key components necessary for human relationships.

This is particularly helpful as one primary goal of intervention and management is to move away from relationships with objects to relationships with people. A non-technical discussion of the levels (and a book that should be read by all who struggle with addiction, therapists, and public policy makers) is The Growth of the Mind: And the Endangered Origins of Intelligence.

For a more technical read, and a detailed discussion of how to assess developmental stages, read Developmentally Based Psychotherapy (note: this link provides you a PDF of the first two chapters which will give you an overview of the stages and therapy – but you will have to buy the book for the appendix that delves into assessment).

Biological Samples/Other Empirical Measures

Very often when conducting a thorough evaluation it is necessary to collect biological samples (e.g., urine, blood) to better assess the accuracy of a client’s self-reporting of substance use, and determine severity levels.

In addition, there are many reliable and valid assessment measures that have been developed for assessing addictive behavior, mental health issues, and other aspects of life functioning. Such assessments are best done by professionally trained clinicians.

Other Evaluation Issues

Great evaluations are somewhat of an art. They require the ability to connect with a client, and explore aspects of their life that often are very shaming – with the aim of uncovering useful leverage points for change.

They also necessitate the ability to know when to seek outside consultation on various issues including neuropsychological impairments and physical health issues that may look like mental health issues. In the end, there are no short-cuts if an accurate, comprehensive, and useful evaluation is the goal.

Putting All the Pieces Together: The Value of Systems Thinking

Critical to effective evaluation is considering how all the various pieces of information collected from a person interact together to manifest the problem behaviors.

To do this, it is useful to have some understanding of systems thinking and the idea of leverage points. Many people continue to struggle – despite countless treatment episodes – because important leverage points for change are never uncovered.

Clinical Examples:

Case 1:

After receiving her 3rd drinking and driving conviction, she was not looking forward to another treatment episode. Boring videos, sitting in groups each week staring out the window, and having to pee in a cup were all a waste of time in her opinion – and something she had done four previous times. And because she had drank within days of getting out of past treatments, why should this time be any different? But then she experienced an evaluation with a therapist that changed her world.

The therapist took the time to get to know her, and although she was asked many questions about her drinking, she was also asked about other objects of addiction and aspects of her life. For the first time ever, Michelle talked about her drinking being a way to help her mask the pain from sexually acting out with men. This led to an even deeper discussion where she revealed to the therapist her history of early childhood sexual abuse.

As the evaluation continued, more and more pieces of her life began to fall into place, and by the third session, Michelle began to see how her underlying trauma history had been playing itself out most of her life – and using alcohol was simply her way to manage the emotional pain.

As the evaluation continued, more and more pieces of her life began to fall into place, and by the third session, Michelle began to see how her underlying trauma history had been playing itself out most of her life – and using alcohol was simply her way to manage the emotional pain.

The therapist also evaluated her level of emotional development, and found that in many ways she was an adult locked in a child’s body. As a consequence of the trauma, her development became extremely constricted and she never gained the developmental skills needed to form healthy, intimate human relationships.

Needless to say, therapy this time did not involve videos about drinking and driving, but focused on:

- Resolving the underlying core issues

- Helping Michelle developmentally catch-up so she could have adult relationships

- Uncovering her natural talents so she could craft a life that was emotionally and spiritually fulfilling

Case 2:

After numerous treatment episodes and little change, Mark was beginning to think that life was about as good as it was going to get. For years he had smoked pot, but eventually this led to experimenting with other drugs, including opioid pain relievers that he originally obtained from a physician he saw for chronic back pain.

His life had seemed to dead-end. He had an extremely boring job, few friends, and knew that most of the time he felt clinically depressed. When he did have opportunities to branch out and engage with people, he became overwhelmed with anxiety. He figured the anxiety had something to do with being obese and not happy with his body.

His doctors had told him he had high blood pressure and was a heart-attack waiting to happen. A few times in his life he felt some momentum for change, but because a junior high-school teacher had told him he had attention-deficit disorder, he decided it must be true and that maintaining a focus on anything was virtually impossible.

The failed treatment episodes over the years just fueled his underlying sense of worthlessness. Then he saw a therapist who spent a great deal of time on evaluation and assessment. Although many of the questions he had been asked before, it was a question in the fourth session that changed his life.

The therapist had noticed that Mark was always nodding off during session, and seemed very tired. In the first few sessions, when asked about, Mark shrugged it off as the result of a hard days work. But by the 4th session, the therapist began to suspect differently. Careful evaluation eventually led to uncovering a suspected sleep apnea. Mark was referred to a sleep disorders clinic that confirmed his apnea was significant, and that for years he had simply had little good sleep.

With this piece of the puzzle, many other pieces fell into place. Because he always felt tired and had little energy, he ate high-carbohydrate/sugary foods to keep his energy up, eventually leading to his weight problems. His lack of sleep also impacted his moods, which he attempted to self-manage with drugs.

Although numerous other issues needed to be addressed in therapy, an important leverage point for change was first focusing on getting good sleep to have the energy to work on the other issues.

What can be learned from these examples:

- Most often people who struggle with addiction have many co-occurring issues

- Just because someone has been to therapy multiple times does not mean that something has not been missed

- Useful evaluations take time, and in the above examples occurred over multiple sessions – not just a 45 intake before proceeding with treatment

- Leverage points for change are often not obvious.

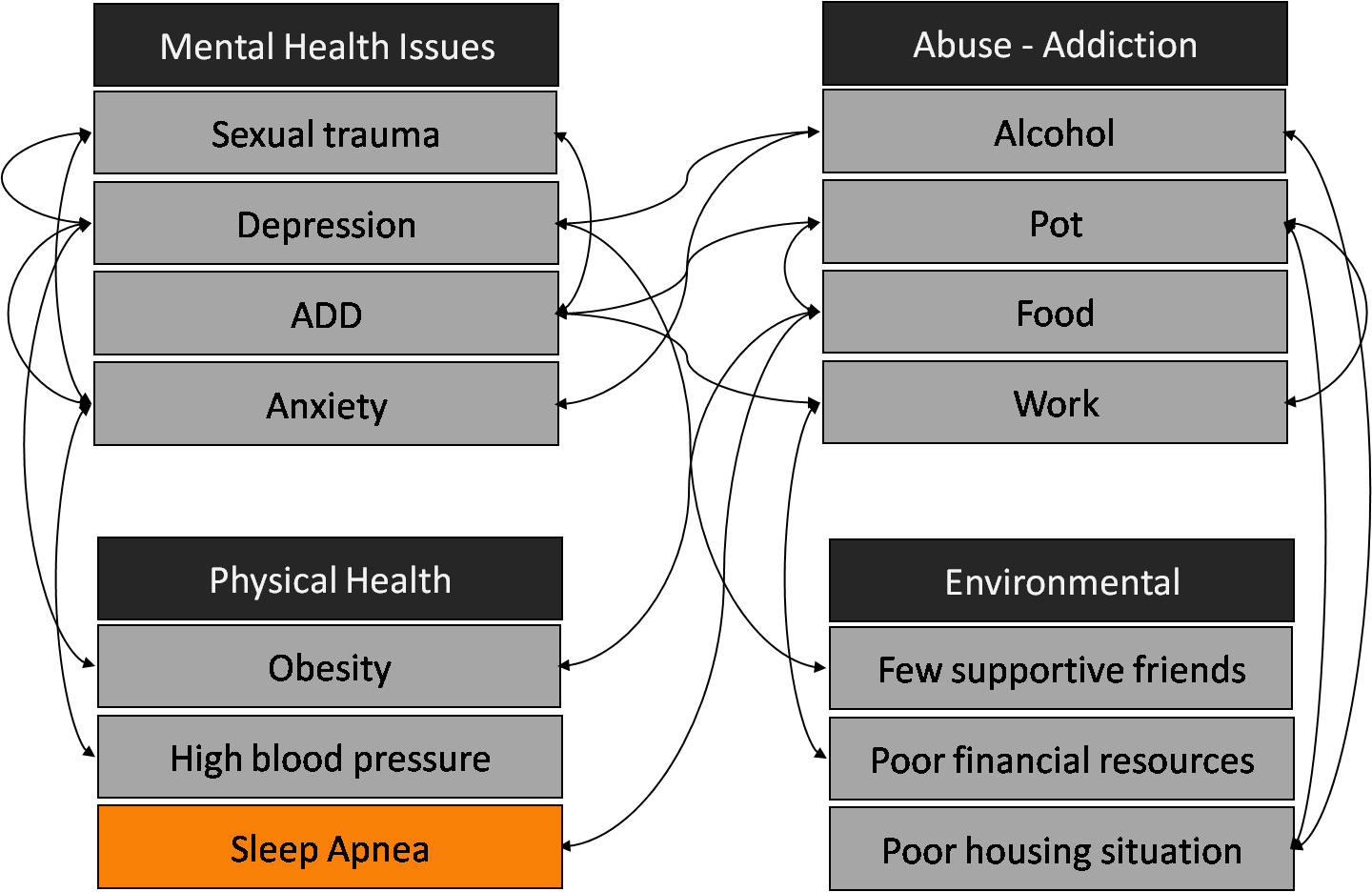

One method for exploring the interaction among the various factors gleamed in an evaluation, is to categorize them into four quadrants:

- Mental health issues

- Abuse/addiction

- Physical health

- Environmental (see below)

As therapist, it is best not to use highly clinical terms if possible, but keep problems in a language understood by the client. Usually the therapist prioritizes the issues in each category prior to a session (see last page of comprehensive evaluation above), and then during the session asks the client how they would prioritize the issues.

It is interesting to note the discrepancy between the way the therapist thinks about a client’s problems, and the way the client sees the priority of their life problems (i.e., almost always there is a difference). Once the client is allowed to reprioritize each issue in the four categories (building motivation for change), then the therapist asks the client to think about how all of the issues interact with one another.

This is where the arrows began to get filled in. It can be very revealing to a client to think about their life systemically, and realize how so many things are connected. In addition, such an exercise reveals important leverage points for change. Instead of writing a treatment plan that addresses each and every issue, it may be that addressing one important factor, such as the sleep apnea in the above illustration, will also impact many other issues that need not be treated independently.

In summary, learning to successfully manage addictive behavior over the life span requires a comprehensive understanding of all the relevant factors that perpetuate the behavior. To date, there are no ideal or optimal evaluation tools, so those struggling with addiction, professional clinicians, and concerned others, need to be aware of the above information, and proactively incorporate it into the comprehensive evaluation.